#70 - How to Stop Self-Sabotage in Conversation

In this episode I attack FOUR of the most common self-limiting beliefs I hear about talking to people. With each belief, we'll unpack why it exists, what it actually is, and how to circumvent it. Remember - I'm not a clinician or licensed psychologist - so I won't be writing any prescriptions or giving that advice. But - I am someone who thinks about communication, talks about it with people nonstop, and wants us all to improve.

Want to watch the video version? Subscribe here: https://www.youtube.com/@TheCommunicationMentor

Have you enjoyed the podcast? If so, follow it, rate it, and share it with three people:

- Follow on Apple Podcasts

- Follow on Spotify

- Follow on Instagram

- Subscribe on YouTube

If you want to share feedback, have a great idea, or have a question then email me: talktopeoplepodcast@gmail.com

Produced by Capture Connection Studios: captureconnectionstudios.com

Welcome to the Communication Mentor Podcast.

This is your host, Chris Miller.

If you've never been here before, first off, it's great to have you.

If this is your second time being here, it's also great to have you.

If it's your third time being here, and over that, I'm gonna start calling you family from now on.

I'll put you on my iPhone favorites.

Just let me know how many episodes you listen to, and that's how I'll put you up on my favorites list.

The purpose of this podcast is for us to grow in our communication so that we can be more resilient to life stress, grow in our careers, and to live fuller lives with those around us.

We believe that life is better when you talk to people, and one of the best investments you can make is to invest in your ability to articulate your thought.

Something that I keep seeing time and time again, and this isn't just in the people around me, but it's in the mirror as well, is four self-limiting beliefs that severely impairs our ability to communicate with those around us.

So in this episode, I'm going to walk through each one of those, explain what makes it such a crippling belief, also unpack why there's actually some merit there, and we need to note this belief.

But lastly, my goal is to remove a self-limiting belief.

I'm not a licensed therapist, I'm not a licensed clinician.

I'm not coming at it from that angle.

Rather, I'm coming at it from, let's actually think about it and take it apart.

For instance, have you ever been in a social setting and thought to yourself, man, I'm about to sound really stupid.

If I open my mouth, then I'm going to sound dumb.

This is one of the most common things that I hear from people is I'm scared to sound silly.

I'm scared that people will think I'm not educated.

Even if I have really relevant, pertinent thought, my ability to articulate is going to hang me up.

And this is the first self-limiting belief.

And the reason why it's so dangerous is that it prevents us from even practicing communication.

We're just doing all this intrapersonal communicating with ourself over and over again.

And one of the things I've learned, self-limiting beliefs grow in darkness.

The way you put light on them is to wrap words around them.

The more words that you begin to wrap around them, the better you can understand it, and the more light you can shine on it.

Whenever you stop talking, or don't even start talking, because you're nervous of sounding dumb, what's actually happening is one, you're preventing yourself from getting practice.

Two, you're maintaining silence, potentially in a moment in which you shouldn't be silent, a moment where you should speak up.

And three, relationships are built on communication.

So if you don't communicate, if you don't voice your thought, you are severely inhibiting a relationship.

Oftentimes, the reason why we have this thought, there's one or two main reasons, but the first, it's something we call maladaptive social cognition.

And it is, think of negative self-talk regarding our ability to interact with those around us.

We don't give ourselves any favors.

We are not gracious with ourself.

We're actually pretty self-critical.

This is kind of messy when you think about it, because if we don't tell anybody that we view ourselves negatively, then other people may not be able to figure that out.

So we can't even get help from people.

The best way to really assess whether or not we identify or whether or not we're in this camp is to journal, is to take note of common thoughts that we are experiencing.

Because if there's something that keeps popping up, there's a reason it keeps popping up and we need to shine a light on it.

The second most common reason why we're scared of feeling dumb is that something's happened in the past and we've gotten burnt.

And it may not have been something that someone did, like it may not have been out of malice, rather it's like touching the hot stove.

We got hurt, maybe some major social embarrassment, maybe we beat ourselves up, like, oh man, that sounded so dumb.

So then because of that, it's a protective mechanism.

And there's merit there, right?

Protective mechanisms exist because we want to survive longer.

But in a social setting, more often than not, people are pretty forgiving.

And that leads us into number two.

And before I hop to number two, let me quickly explain how to deal with this.

And I think the best way for us to deal with this is to reframe what we view as stupid or dumb.

When you really think about it, the most dumb thing we could do is not articulate our thought or speak up for ourselves.

Because in the long run, we are really putting our, we're getting in our own way.

That's super stupid.

Also, a lot of the stuff that we think is going to sound dumb, the social sting will not last as long as we think it will.

And the reason why is, well, the second self-limiting belief, and that's, everybody is going to be thinking about what I'm saying, people are looking at me, man, if I'm thinking this, other people are thinking it.

An extension of the first, and that's we can't read each other's minds.

Our minds are social cognitive machines.

We are either more than likely thinking about a conversation we're about to have, a conversation we're currently having, or a conversation we just had.

Oftentimes, our anxiety is rooted in relational issues.

Something's going on with our family, a romantic interest, a friend at work.

Our mind is dedicated to read thousands and thousands of microgestures and faces.

We calculate without even knowing emotion.

We calculate nonverbal language.

We can sense tonality, pitch, pacing, silence.

All of this, we put together in our brains, and from it, we're able to say, okay, she's a little upset, or he's a little excited, or honestly, he sounds a little self-defeated.

All of this is happening, and due to that, something we're really not thinking about is analyzing every single person's words if they speak to us.

Because if you catch that on the distractibility of what's happening in our current world, the digital immersion, the fact that our brains are currently being hacked by perpetual dopamine-emitting elements, if you really think that you can retain everything you watch on TikTok or on YouTube shorts, on Instagram reels, think again.

I challenge you to tell me 10% of what you've seen in the past week on any of those platforms.

We can't retain it because our brains weren't made for that.

So whenever we're in social settings, we have to care a lot less that people are paying attention to us so that they're going to be talking about us later because honestly, they don't have the mental bandwidth.

The majority of people don't have enough mental bandwidth to check in with the current relationships they have enough to the point where the other person feels really appreciated.

We just don't have that mental bandwidth.

The reason why a lot of us think this is, again, it's a protective mechanism.

We need to know when a whole bunch of people are staring at us because it's odd.

That means that there's something about us that's attracting a lot of attention.

Maybe in our modern day, attention is a good thing, but historically, attention was a really controversial thing.

There's a big chance it was bad.

If you were the, what's that phrase, like the squeaky wheel, in a tribe of 70 people, and you got a little social tension, and there was social angst, and you're the culprit of it all, it was not good for you because if you got removed out of that group, you were going to have a terrible time trying to survive.

We are social creatures, and we live in a social organism.

The network is necessary.

So attention, historically, some of it was good.

Like if you're the champ, that was great.

But it's an unsure thing.

So that's a little bit of why it's not wiring.

That's my assumption.

And I think the way that we get about this is by telling ourselves, how often am I thinking about the people who interact with me?

Like sure, I may be thinking about them whenever I'm talking to them, but after the fact, am I thinking, ha ha, like he said this, he said that?

More than likely, the answer is no.

Because more than likely, you have a bill to pay, you have a job you need to go to, a romantic partner you have to go back home to, a house you have to clean, a lawn you have to mow, edges you have to weed.

There's so much going on in our brains.

We can give ourselves a little grace.

Which leads me to number three, because sometimes, this is a weird phrase, but let me explain it.

Sometimes we almost give ourselves a little too much grace.

And grace probably isn't the right word to use in this spot.

But what I mean is we think that we know the most so that, and because of that, we don't stop talking.

We think we're going to be able to contribute all the value to the conversation.

When really, what this prevents us from doing is listening.

There may be several reasons why we think this.

We may have grown up in a home, or we're the only child, and we always had a captive audience, and everybody was always wanting to listen to us.

Or it may be the other end.

Maybe we grew up in a home where we didn't get any attention.

But now, whenever we're in a conversation, we have a captive audience, and then we can go and talk as much as we can to try and get as much attention as possible, because we're at an attention deficit.

And it may not be any of those, right?

It may be you feel as if you're an expert on a topic, and whenever that topic pops up, then you're like, all right, they're giving me the green light.

Time to go at them.

But the truth is, most conversations, I would say 99% of conversations, there may be, especially in a personal one-on-one conversation, not involving a platform.

I would say potentially like consulting, counseling.

There are a few situations where the listener is a prescribed position in conversation and interaction.

But other times, or most times, that's not the case, and we need to listen.

So rather than us feeling as if we have something dumb to say, we overcorrect, and we get to the point where, nope, like the other person won't be able to add any value to this conversation, which inhibits us from having full, substantial conversations, because like we've talked about a few times, the communication model, it's cyclical, starting with the sender going to the receiver.

The sender sends a message, but when they do that, they encode their message, and then the receiver has to decode that message.

So if you tell me, no, I'm okay, and that's the message you encode, and I decode it like, I don't think he's okay.

I don't think he's fine.

If you tell me, I'll eat wherever, and then I'm decoding that like, I think he has somewhere in mind to eat.

We have to do this cyclical conversational turn-taking.

So if we cut half of it off, if we're no longer listening, then the amount of meaning collaboratively we create with our communication, it starts to, what is it, stagger, winnow.

It goes down and down and down.

It narrows.

The way for us to go about this is to be a little bit better at assessing the environment and assessing the situation.

Is it expected for me to talk 99% of the time, even if the person that you're speaking with is not the easiest person to talk to, even if they have a hard time articulating their thought because they may be on the other side of the camp to where they're so nervous they're going to sound dumb?

Even in that situation, you have to be quiet for long enough to give them the room to speak up.

Make them uncomfortable that they're not talking.

Get them talking.

I remember in undergraduate, I had a mentee, and this mentee was kind of like a mentor to me for some things.

Typically, that's how it works.

But I noticed that I talked most of the time during our weekly meetings.

So there was a moment where I said to myself, like internally, I'm talking to myself while I'm talking to him, all right, Chris, you're going to have to shut your mouth to hear what he's going to say.

So I did it, and I waited, and it was uncomfortable.

And we waited, and we waited, and I looked around.

I tried to buy time with my nonverbals, and then he said, so do you play cards?

And I was like, no.

And he started to talk to me about this passion he had I didn't know he had, because we never talked about it.

But I never would have guessed, I never would have figured that out had we not had that talk, and had he not spoken up, and had I not given him the room.

So get better at assessing the situation.

Recognize whenever you talk a lot.

Typically, it's hard, because if we did recognize that, we'd stop talking, but use this as another nudge to take some self-assessments every now and then.

And that leads me to the other limiting belief, because as we're taking these self-assessments, at some point, we're gonna have to turn the analytical brain off.

The more you learn about communication, the more you learn about social psychology, the more you learn about human behavior, you begin to index your normal interactions.

You begin to have a rubric or have a lens that looks at tonality, that looks at pacing, that looks at word choice, that looks at gesticulation, the active use of hand gestures, the active use of waving arm gestures.

You begin to look at everything.

And the reason why this is a negative, it's a deterrent on our relationships and our ability to strike up conversation and really be a part of good conversation is we start reading too much.

We start looking too far into what's going on.

It removes us from being present.

We put on our lab coat whenever we should have our seatbelt on.

We should be worried about not falling out of the conversation rather than be worried about testing what's going on inside the conversation.

Think about the social experiment with the camera and the YouTuber and him going up to there and getting a good bit of content and then leaving.

If you're the other person on the other side of that, there wasn't a good conversation had more than likely, and you don't really feel like you gained anything.

Maybe they asked you if they could put you on YouTube, and you're like, oh, cool, I'm going to be on YouTube.

But that's an example of people getting into an interaction or a conversation with the end goal in mind and assessing it to try and get there.

We have to turn off the analytical.

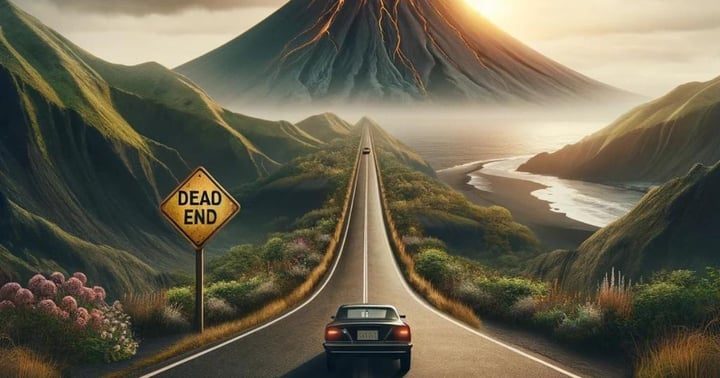

The reason why it could be good at some points is for us to know whenever we're getting to dead ends, whenever we're doing something that's going to prevent us from having a conversation, we can self-correct.

And the way that we can get out of it is by simply taking a breath and focusing on what's the present moment instead of trying to connect it to the studies and the patterns that we've seen, just being able to be there and smile and focus on the last sentence that was said.

If you catch yourself focusing on things that happened like 10 minutes ago, 15 minutes ago, and getting your mind in a different place, then you'll ultimately lead the conversation, not gaining as much, because you weren't present.

So I challenge you, if you feel like you're going to say something dumb, speak up.

Don't bottle all your thoughts in.

If you feel like everybody's looking at you and thinking about you, and they're going to be talking about you the next week, think again.

They're thinking about things they don't even know they're thinking about.

The things they wish they were thinking about, they can't think about, because they've bombarded their brains with so much.

That maybe you and I, and we need to make sure we do our best to take a break from the screens, to take a break from the tasks, to take a break from the productivity.

If we keep talking and we're not listening, we are shooting ourselves in the foot.

The best, and I underline best, communicators are active listeners, and more than likely, even though they're incredible at articulating their thought, unless it's a time and a place for them to be doing most of the talking, they're listening.

And lastly, it is okay to be thinking about conversation.

It is not okay to consistently analyze it.

You need to turn it off, and you need to be present.

If this added you any value, I encourage you to share it with one person.

If you haven't already, rate and review the podcast.

It is a pleasure to be able to produce podcasts like this, and I will see you on Monday.

![#13 - Exploring the Intersection of the Mental Health and Criminal Justice System [RICK CAGAN] #13 - Exploring the Intersection of the Mental Health and Criminal Justice System [RICK CAGAN]](https://storage.buzzsprout.com/variants/8p2f1mi7kb94vnie2vzt23npodxh/60854458c4d1acdf4e1c2f79c4137142d85d78e379bdafbd69bd34c85f5819ad.jpg)

![#77 - Uncovering the Secrets of American Friendships in 2024 [Harvard Visiting Scholar, Dr. Jeff Hall] #77 - Uncovering the Secrets of American Friendships in 2024 [Harvard Visiting Scholar, Dr. Jeff Hall]](https://storage.buzzsprout.com/81064p22y0fwwiok7vdj87clj7vt?.jpg)